Generating 3D Assets for Digital Twin Robotics Environments

Introduction

In this blog we explore how modern generative models and simulation tools are changing the way we build digital twins for robotics. Instead of manually modeling every single object, we rely on a mix of prompt based image generation, 2D to 3D reconstruction and scene composition pipelines. Using techniques such as 3D reconstruction from images with SAM 3D, combined with NVIDIA Omniverse and Isaac Sim to assemble and simulate entire environments, we can turn simple descriptions and reference photos into large, diverse libraries of 3D assets. This synthetic data pipeline makes it possible to populate complex job sites in days instead of months, while keeping the sim-to-real transition as smooth and reliable as possible.

Why realistic digital twins are still hard

Digital twins strongly depend on the quality and diversity of their assets. 3D objects need plausible geometry, materials, lighting and physics to approximate the messy, imperfect environments where robots actually operate. In many robotics projects, however, simulations end up looking like showrooms: idealized layouts, perfectly clean textures, a handful of repeated CAD models, and almost no clutter or human activity.

%2010.04.28%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

On the other hand, collecting real data at scale is expensive, logistically complex and sometimes unsafe. Filming near heavy machinery, staging risky situations or asking operators to repeat rare edge cases is usually not an option. Even when you manage to capture that data, annotation becomes a bottleneck.

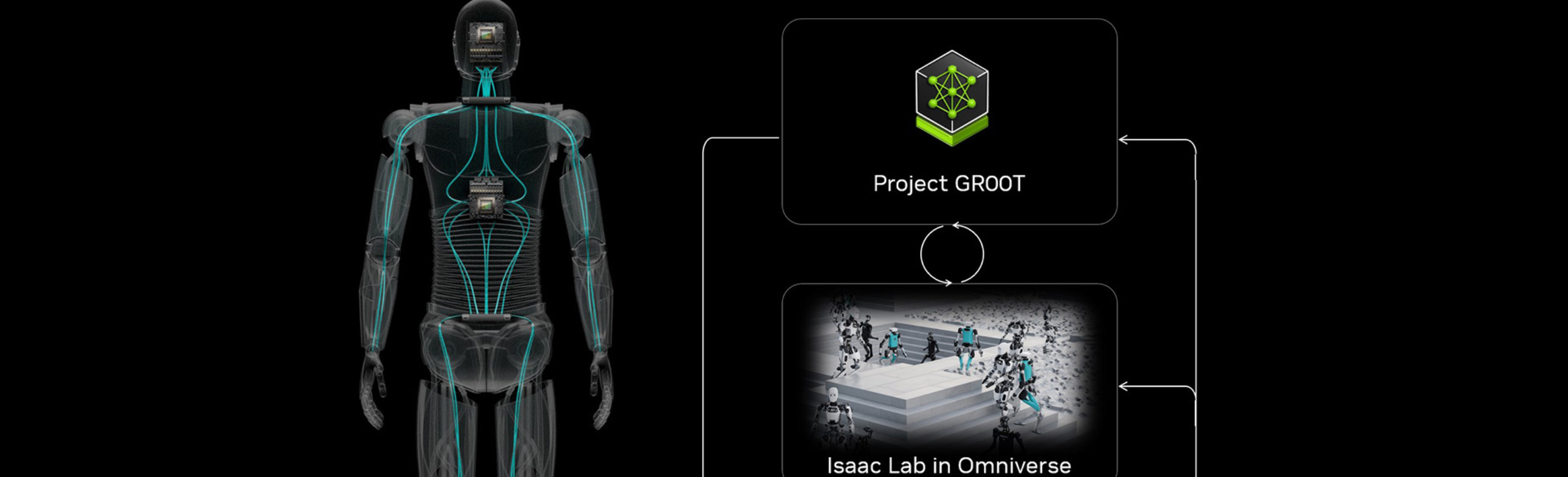

Synthetic data addresses part of this gap, especially when combined with engines like Isaac Sim that can render realistic environments and automatically produce annotations such as bounding boxes, segmentation masks or depth maps. But there is a question that often remains underexplored: where do all the objects in those synthetic scenes come from, and how do we make them varied enough to matter?

From static CAD libraries to generative synthetic assets

The traditional answer is straightforward but slow: a 3D artist or engineer models every asset by hand, usually starting from CAD files or concept art. Those assets are then imported into the simulator, tuned, reused and gradually expanded. When you need a slightly different traffic cone, a more damaged pallet or a new type of barrier, you either spend more time modeling or you compromise and reuse what you already have.

%2010.05.34%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

Generative AI allows for a different approach. Instead of sculpting every detail manually, we can start from text descriptions or reference photos, generate images that depict the objects we care about, and then reconstruct those objects in 3D. SAM 3D gives us a way to “lift” segmented objects from images into meshes, while Nvidia Omniverse Isaac Sim provides the backbone where those meshes become part of full environments, complete with lighting and physics.

%2010.12.47%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

The result is a pipeline where the unit of work is no longer “build this asset from scratch” but “describe the object, generate a few images, and let the reconstruction and simulation stack do the rest”.

Step 1 – Generating diverse reference images

The pipeline usually starts with natural language describing the objects and scenarios we need like “A cone that is dirty and slightly deformed, a safety barrier with reflective tape under harsh sunlight, a worker wearing a yellow helmet and an orange vest, a stack of pallets in the shadow of a machine, and so on”. These descriptions feed into text to image models that produce candidate images.

A practical insight that emerges quickly is that trying to place too many different objects in a single image tends to dilute detail. Workers, cones and tools become small elements in the background, which is not ideal for later reconstruction. It is more effective to generate images where each object of interest occupies most of the frame and is seen from a clear angle.

Once we have some good base images for a class of objects, we iterate. We tweak prompts to change textures, levels of wear and tear, lighting conditions or viewing angles, asking for variations of the same concept and generating examples in slightly different contexts. The goal is to end up with a small set of high quality, diverse images for each type of asset.

These images are not yet part of the digital twin, but they form a rich visual catalog from which 3D assets can be derived. A few examples are shown below.

Prompt Image 1: A realistic photograph of a single, new orange traffic safety cone standing upright on clean asphalt. The cone is vibrant and clean, with a pristine white reflective collar. The background is a blurred paved road under bright daylight.

Prompt Image 2: A macro photograph of a single orange traffic safety cone sitting on rough dirt. The plastic surface is scuffed, dirty, and faded from sun exposure. The reflective white collar around the middle shows cracks, peeling, and grime. Sharp focus on the texture of the cone, blurred construction background.

Prompt: "Based on the 'real image' on the left, generate a photorealistic depiction of the traffic barrel where it appears brand new. The orange plastic should be glossy and flawless, with clean, sharp white reflective bands and a pristine black rubber base, completely removing all original scratches, dirt, and wear while keeping the background and lighting identical."

Prompt Image 1: A detailed medium close-up photograph of a construction worker, similar to the one in image_6.png, actively operating a heavy jackhammer. He wears a white hard hat, sunglasses, a bright yellow high-visibility safety vest over a blue shirt, dark work jeans, and gloves. Dust and dirt billow around his boots and the jackhammer bit as it breaks the ground. The background is a blurred construction site with soil piles and traffic cones, but the focus is sharp on the worker and his tool. Golden hour lighting.

Step 2 – From pixels to meshes with SAM 3D

The next step is to transform those images into 3D geometry that a simulator can understand. This is where SAM 3D comes in. Building on the idea of segmenting arbitrary objects in an image, SAM 3D lets us select a region of interest and reconstruct a corresponding 3D mesh.

%2010.29.20%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

Example of a 2D-to-3D reconstruction workflow using SAM 3D. The object on the left is segmented from the input image, and SAM 3D generates a corresponding 3D mesh shown on the right, which can then be refined and prepared for simulation.

The workflow is conceptually simple. We load one of the generated images, indicate the object we care about, and let SAM 3D infer a 3D shape. The output is typically a mesh in a format such as .ply for generic objects. For more complex entities like human figures, the reconstruction can include richer information, for example encoded in .GLB files that carry geometry and basic material data together.

We repeat this process for several images and variations of the same category, cones in different states, barriers with different colors, workers with different equipment. Not every reconstruction will be perfect; part of the work is to visually inspect the results, discard meshes that are clearly unusable, and keep those that capture the essence of the object with sufficient fidelity for simulation and perception tasks. Below are a few representative examples.

Video 1:https://aidemos.meta.com/segment-anything/gallery/?template_id=832850682964027

Video 2:https://aidemos.meta.com/segment-anything/recents/?template_id=198023664608999

Video 3:https://aidemos.meta.com/segment-anything/gallery/?template_id=2722125464791925

Video 4:https://aidemos.meta.com/segment-anything/gallery/?template_id=822533564022314

For human figures, one important requirement is that the body is not cropped or heavily occluded in the image. In fact, this is desirable for any type of object, since full visibility helps the reconstruction model infer a coherent overall shape that can later be refined or rigged if needed. Even if the result is still a rigid body at this stage, it is already useful for many computer vision workloads, such as pedestrian detection or safety monitoring.

2: https://aidemos.meta.com/segment-anything/gallery/?template_id=3281647291993341

Step 3 – Cleaning and preparing assets for simulation

Meshes produced by reconstruction models are a strong starting point, but they require some post-processing before being used in a simulator. This is where 3D modeling tools such as Blender come into play. The typical cleaning pass includes checking and adjusting scale so that objects have realistic dimensions, aligning orientation and defining a sensible pivot point (for example, at the base of a cone), and simplifying or fixing problematic topology. Small defects that are irrelevant in a rendered image can become significant once physics and collisions are involved.

During this phase we also standardize formats. Since Omniverse and Isaac Sim are built around USD as a core representation, we convert cleaned meshes into USD assets and, when useful, define variants that encode different appearance or configuration options. This lays the groundwork for instancing and efficient scene assembly later on.

%2010.45.24%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

Reconstructed 3D asset loaded into Blender for cleanup and preparation before export to USD.

At the end of this step we have a curated, simulation-ready asset library: not perfect, but consistent, correctly scaled and compatible with the rest of the digital twin stack.

Step 4 – Building synthetic scenes in Omniverse and Isaac Sim

With a library of assets in USD, we move to Nvidia Omniverse Isaac Sim to construct actual environments. Cameras, lights, ground planes and larger structures define the basic stage and generated cones, barriers, tools and workers populate that stage.

If you already have scripts that control object placement, camera motion and annotation generation in Isaac Sim, those scripts do not need to change dramatically. The main difference is that instead of instantiating a handful of generic primitives, you now instantiate a diverse catalog of realistic objects. Positions, orientations, textures and lighting can be randomized to produce hundreds or thousands of unique views.

Because Isaac Sim is tightly integrated with the physics and rendering capabilities of Omniverse, you can decide how far to push realism. For some use cases, simple rigid body behavior and approximate materials are enough but you can invest in more detailed physical properties, better shaders or richer lighting setups. The key is that the pipeline scales, once the assets are defined, creating a new dataset becomes more a matter of parameterizing the scene than of hand tuning every shot.

The outcome is a large set of synthetic images, paired with high quality annotations, that better reflect the variability and clutter of real jobsites compared to traditional, clean simulations.

%2010.47.28%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

People and safety

One of the most compelling applications of this approach is the modeling of human presence and behavior around machines. For safety and critical systems, it is essential to recognize people in different positions, with different equipment and, sometimes, in non compliant situations.

By generating images of workers with varied clothing, body types and personal protective equipment, reconstructing them with SAM 3D and bringing them into Isaac Sim, we can create scenes where people appear in safe zones, in borderline areas and in places where they clearly should not be. We can also represent missing helmets, partially visible bodies, occlusions behind obstacles and other challenging conditions.

Recording these situations in the real world would be risky and ethically questionable, synthesizing them in a controlled virtual environment is both safer and more flexible. Models trained on such datasets are better prepared to detect pedestrians, enforce safety rules and generalize to the visual diversity that real operators exhibit.

%2010.49.42%E2%80%AFa.%C2%A0m..png)

Advantages and trade-offs of generative synthetic pipelines

Moving from fully manual asset creation to a generative synthetic pipeline brings clear benefits, but also some considerations that teams need to keep in mind.

On the positive side, the most obvious gain is speed. Generating a family of assets from text descriptions and images is significantly faster than modeling each one from scratch, especially when variations in texture, wear or minor geometry changes are required. The pipeline also offers much greater diversity, by tweaking prompts and reconstruction settings, it is possible to explore a wide space of appearances and conditions, including rare or adverse situations that are hard to capture on camera.

Another advantage is reusability. Once the steps from description to USD asset are in place, the same process can be applied to new domains, warehouses instead of construction sites or agricultural fields, without reinventing the workflow. The stack of generative models, SAM 3D, geometry cleanup and Omniverse / Isaac Sim acts as a general engine for synthetic content.

On the other hand, there are trade-offs. Reconstructed meshes are usually not as precise as handcrafted models, particularly for highly engineered components where exact geometry matters. For many perception tasks this is acceptable, but it is important to be aware of the limitations. In addition, physics and material properties are not magically inferred, they need to be configured, either in the modeling tool or inside Omniverse, to behave realistically under simulation. Finally, relying solely on synthetic data can introduce biases linked to the generative models themselves, so it remains critical to validate performance on real data and, when possible, mix synthetic and real samples.

Designing for smooth sim-to-real transfer

The goal of all this work is not simply to generate beautiful renderings, but to train models and develop control strategies that transfer to real systems. Achieving that requires deliberate attention to sim-to-real alignment.

At the visual level, camera intrinsics, fields of view and mounting positions in simulation should match those on the physical robots as closely as possible. Lighting conditions in synthetic scenes should span the range seen in deployment: bright sun, overcast days, artificial illumination, shadows and glare. Object scales and placements should reflect actual constraints and layouts.

At the data level, it is usually best to combine synthetic and real samples. Synthetic data gives you coverage and diversity, while real recordings anchor the model in the true distribution of textures, noise and imperfections. By evaluating models on a separate set of real-world footage, tracking missed detections of pedestrians, localization errors for objects and false alarms in safety scenarios, you get actionable feedback to improve both the synthetic generation pipeline and the training setup.

When this loop works well, the generative asset pipeline becomes a powerful lever: it allows teams to iterate quickly on environment design and safety logic, while keeping the ultimate objective firmly tied to real-world performance.

What comes next

It is not hard to imagine a near future workflow where a product owner specifies, in natural language, the kind of site they want to model, its size, topology, machinery, traffic patterns and safety rules, and an AI agent orchestrates the whole chain: designing prompts, generating images, reconstructing assets, cleaning geometry, assembling scenes in Omniverse and launching synthetic dataset generation in Isaac Sim. Human experts would focus on defining objectives, constraints and evaluation criteria, rather than on manually placing cones and barriers.

At Marvik, we are already working at this intersection of generative AI, digital twins and robotics, helping teams use synthetic data to accelerate development and improve safety for machines that operate in complex environments. If you are exploring how to train robots in realistic virtual worlds before sending them into the field, we would be happy to talk.

.png)